"Tradition, for me, has always been contemporary. It’s not a contradiction."

Ahmad Angawi lives inside that sentence. He is an artist of the now who refuses to abandon the language of before. In Saudi contemporary art, few practices feel as physically intimate and as socially expansive as his. Work rooted in the Hijaz, where tradition is treated like a working system: translated through geometry, material intelligence, and human stories, and expanded into installations that invite the public to step in, contribute, and connect.

Meccan Roots and a Philosophy of Balance

Angawi is a multidisciplinary creative from Makkah, shaped by the cultural density of the Hijaz and influenced by his father, the architect Dr. Sami Angawi. In Angawi’s language, craft is not nostalgia. It is a philosophy of balance, often described through the concept of Al Mizan: a search for equilibrium that is spiritual, architectural, and human.

That duality shows up in his education too. Industrial design at Pratt Institute in New York, then traditional arts at The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts in London. The pairing matters. One trains the eye for systems, prototyping, and contemporary materials. The other trains the hand and the conscience.

Street Pulse and the Sound of a City Speaking

Angawi’s breakthrough language is not purely visual. It is participatory, civic, and unapologetically about people. Street Pulse, begun in 2012, is one of his most widely cited works. An interactive installation that collects recorded voices and personal stories from the streets of Jeddah, framing public speech as a living vital sign. The piece can be described as an electrocardiogram for the city: not measuring the body’s vitals, but the pulse of the street, with silence equated to flatline.

"I always want to create objects and art that help people with their lives and make a difference,"

Mangour as a System of Light, Privacy, and Design

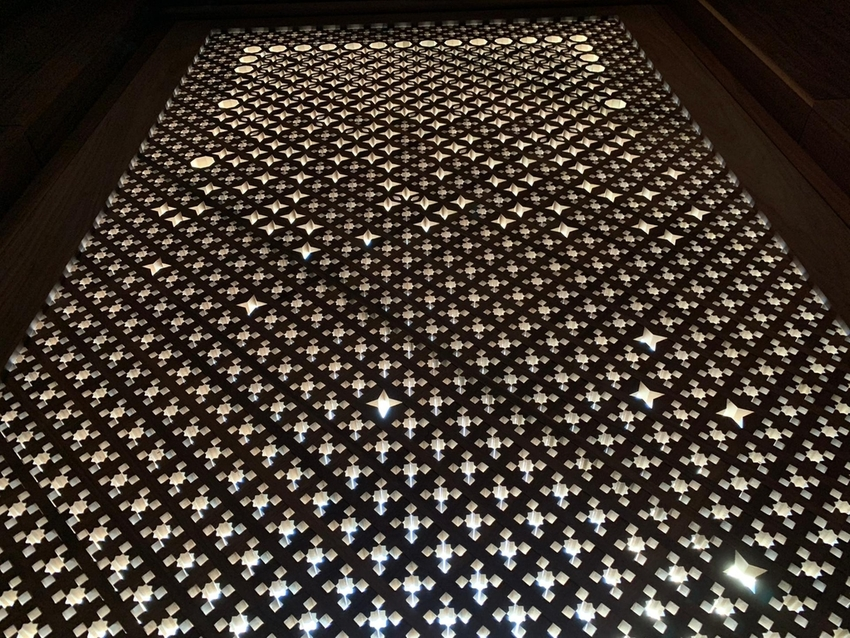

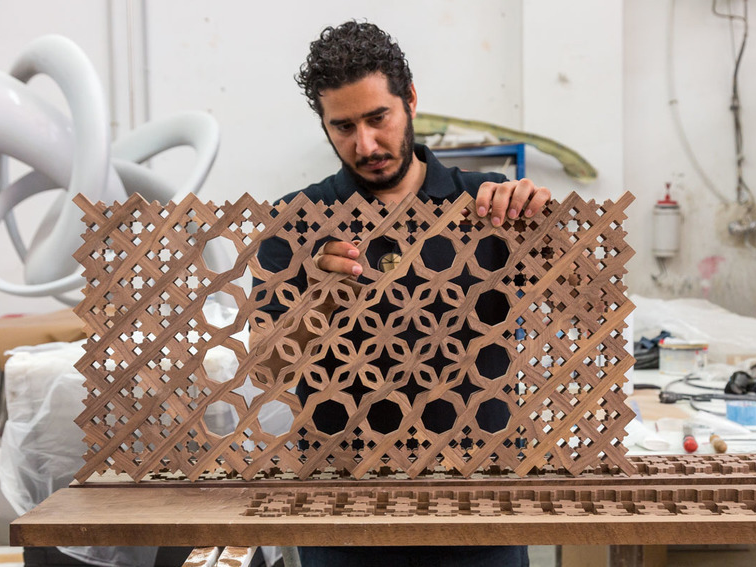

If Street Pulse is Angawi’s social architecture, Mangour is his material philosophy. Mangour is a traditional Hijazi wooden latticework associated with roshan and Hejazi facades, designed to filter light and protect privacy. Angawi returns to it not as ornament, but as intelligent design: a technology of climate, shade, dignity, and domestic life.

This is where Angawi becomes globally legible without flattening himself for a global audience. In 2017, the British Museum selected him to create a permanent, site-specific work for its Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World, inaugurated in 2018: five mangour window screens in black walnut wood, produced through a deliberate blend of digital fabrication and handcraft. His insistence on integration is part of the piece’s ethics. He has spoken about wanting the work to be a meeting point between London and Makkah, avoiding the gesture of simply transplanting culture.

Light as a Medium, Not an Effect

Angawi’s relationship with light is architectural: light reveals structure, it does not decorate it. At Noor Riyadh (2021), his work Proportion of Light highlighted mangour’s origin and function, describing it as a complex architectural element made from an interlocking wooden lattice system that creates a patterned surface and net-like veil in the interstice spaces.

Even when he steps into contemporary light art, the source code stays Hijazi: craft, proportion, and the social behavior of space.

Flow and The Study of Time Inside Materials

Angawi’s practice also moves through fluidity: not only metaphorical, but literal. During his 2017 residency at Delfina Foundation in London, he continued developing Flow, an installation built from colored liquids and PVC tubes. By 2019, a version titled Flow #2 appeared in the Ithra exhibition Zamakan, positioned within a curatorial frame of space and time, and described as transparent PVC tubes with liquid motor and variable dimensions. There is a quiet through-line here: whether he is working with microphones, wood, or liquid, he is always sculpting living systems.

Zawiya 97 and the Return to Al Balad

Angawi is not only an artist. He is also a builder of cultural infrastructure. He founded Zawiya 97 in Al Balad, Jeddah’s historic district, framing it as a hub for artists, designers, and craftspeople, with a focus on reviving traditional crafts and activating the neighborhood’s creative ecology. The name is intentionally layered: tied to the 97-degree angle from Jeddah to Makkah.

For Angawi, tradition is something that has to stay alive, taking in what people need today and returning it as new, practical answers. He often frames making as a full-bodied experience, one that aligns mind, body, and soul, and he treats wood as a living material that teaches patience through its natural limits.

Zawiya 97 carries that same spirit on the ground: nurturing artisans through hands-on support, and keeping Al Balad active through workshops, residencies, and community gatherings. In the wider story of the district’s revival, Angawi and Zawiya 97 sit at the heart of a return that preserves heritage while energizing a contemporary creative economy that still feels unmistakably local.

Education, Institutions, and the Craft of Transmission

Angawi’s role as an educator is not a side note. It is part of his medium. He has been associated with the Jameel House of Traditional Arts in Jeddah, an initiative connected to The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts and Art Jameel, and he appears as a local master in Art Jameel’s program communications. This matters because Angawi’s work is fundamentally about transmission: how knowledge moves from hand to hand, street to street, generation to generation.

Recent And Upcoming Work

Right now, Angawi’s practice is traveling by design, moving across Saudi public platforms and into international contexts, while staying loyal to one idea: heritage is a living system, not a fixed image. In Noor Riyadh (2025), Algorithms of Light: The Falcon draws on Najdi Sadu geometry and falcon iconography to explore motion, tradition, and transformation through light. His reach also extends into Expo 2025 programming at the Saudi Arabia Pavilion’s cultural arts studio, where he developed new work aligned with his philosophy of fusing cultural practices through making.

And in Uzbekistan, that same logic becomes almost medicinal. Created for Bukhara Biennale 2024 to 2025, The Algorithm of Healing: Al Jabr & Al Jazr threads together the legacies of Al Khwarizmi and Ibn Sina, turning algebra’s roots into a metaphor for restoration. A traditional wooden panjara screen anchors the work, while colour and movement unfold behind it in a coded rhythm, proposing healing as something built from craft, knowledge, and cultural continuity.

Heritage as a Future Tense

Angawi’s practice refuses the easy binaries that still haunt global conversations about Arab art: tradition versus modernity, craft versus concept, community versus institution. His most consistent subject is the human condition as lived through place: how people speak, how light enters a home, how a city remembers what it once knew.

And perhaps that is his signature: he does not make objects that end the conversation. He makes systems that invite it.

Inspired by Ahmad Angawi?

Explore more artist stories at KSA Art.