For over 33 years, Ibrahim Al-Almaai has quietly traced the heartbeat of a heritage at risk of being forgotten. Across the undulating terrain of Saudi Arabia’s Asir region, he has walked from village to village, home to home, in search of a vanishing tradition: Al-Qatt Al-Asiri. A geometric, symbolic mural art historically painted by women on the interior walls of their homes.

“My mission has always been to find and preserve what time and weather have tried to erase.”

A native of Asir himself, Al-Almaai grew up surrounded by the sights and sentiments of this art form. Even as a young man, he recognized its fragile nature, how tradition, if left unrecorded, might quietly fade beneath the weight of change.

Rather than view this as a loss, Al-Almaai saw it as a calling. He understood that every pattern carried memory, that every brushstroke was both artistry and archive. And so he made a vow: to seek out what endured, to listen to the stories etched into walls and woven into textiles, and to preserve them with care.

What Is Al-Qatt Al-Asiri?

Al-Qatt, also known locally as Al-Katba, Al-Naqsh, or Al-Zayan, is more than decorative art. It is a visual language passed down through generations of women in Asir, each pattern a quiet chronicle of identity, memory, and domestic ritual. And it was women who held the knowledge, who painted their walls as a means of both self-expression and cultural preservation.

Mapping a Disappearing Legacy

Al-Almaai isn’t merely a visual artist. He is a cultural archivist, a documentarian with a painter’s eye. Over more than three decades, he has cataloged over 1,200 variations of Al-Qatt patterns and color compositions, painstakingly recording what might have otherwise slipped into obscurity.

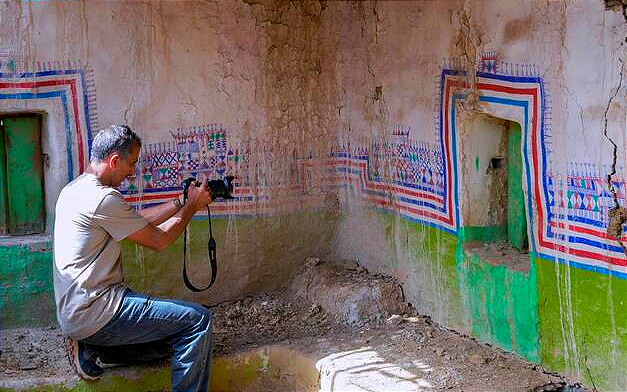

Week after week, year after year, he ventured through the eastern, western, northern, and central parts of the Asir region. Each home he entered was both a discovery and a farewell: remnants of Al-Qatt patterns gracing forgotten corners, colors faded by sun and time, stories embedded in pigment.

Dissecting the Design Language of a Heritage

Al-Almaai’s contribution is not just about saving images. It’s about understanding the structure behind them. Through his studies, he has identified four foundational components that appear consistently in traditional Al-Qatt-adorned homes:

- Al-Shabaka (the Network): Interlaced single-color lines that form the foundational structure of the mural. These lines act as the scaffolding upon which the rest of the composition is built.

- Al-Hanash (the Snake): Serpent-like motifs inspired by the Coluber snake, introducing movement and fluidity amidst the rigidity of the grid.

- Al-Khatmah / Al-Akhtam (the Seal): These visual closures signify the end of a design pattern, like the final verse in a poem, they bring a rhythmic completeness.

- Al-Qatt (the Lines): Foundational horizontal strokes often layered beneath the central designs. Known by different names depending on local dialect, Al-Katba, Al-Naqsh, or Al-Zayan, they carry both aesthetic and symbolic weight.

These aren’t just decorative elements. In Al-Almaai’s hands, they become an alphabet of memory.

From Private Walls to Public Recognition

Though Al-Qatt Al-Asiri was long practiced in private, domestic spaces, passed from mother to daughter in village homes, it gained global attention in 2017 when UNESCO inscribed it on its list of Intangible Cultural Heritage. This recognition was a moment of validation for an entire culture, and artists like Al-Almaai have been central to that movement.

His efforts have not gone unnoticed. Media outlets have highlighted his devotion, describing his weekly journeys into villages and his role in safeguarding the tradition. But his fame is quiet, grounded in service rather than showmanship. He captures, he paints, he preserves.

A Practice Rooted in Respect

Al-Almaai’s reverence for the art form extends beyond the visual. He understands that Al-Qatt Al-Asiri is a matrilineal practice rooted in women’s stories, rituals, and creativity. His role is not to claim ownership but to create bridges: between generations, between regions, between past and future.

He has spent years building trust in local communities, ensuring that his work is not seen as extraction, but as preservation. The homes he visits often no longer belong to the original families. Still, he enters with humility, sometimes finding only a fragment of a once-grand mural, but always treating it as treasure.

Cultural Memory in a Changing Landscape

Today, Al‑Almaai’s work shines brighter than ever. In the midst of Saudi Arabia’s vibrant modernization, questions of identity and cultural continuity naturally emerge. What do we cherish, and how do we celebrate our past?

In this context, Al-Almaai’s paintings and studies are answers. They tell us that beauty was always here. That design lived in the hands of women whose names may be lost, but whose geometry remains. That tradition is not static, but can evolve, so long as it is remembered.

A Living Archive

While he has not sought the spotlight, Al-Almaai’s body of work stands as a living archive. His studies have influenced younger artists and designers, inspired curators, and guided cultural researchers interested in the roots of Saudi aesthetics.

And perhaps most importantly, his work reminds us that preservation is not passive. It is active, dynamic, and deeply personal.

Why It Matters

Ibrahim Al-Almaai’s legacy is not measured in exhibitions or accolades, but in the thousands of patterns, colors, and stories he has rescued from oblivion. He has given shape to silence, form to forgotten artistry. He is a bridge between the intimate and the institutional, between women’s domestic expressions and global recognition.

In the quiet pulse of Al-Qatt Al-Asiri, he has found a calling, and through his devotion, Saudi Arabia finds a mirror to its soul.

Follow his journey on Instagram and X.

Inspired by Ibrahim Al-Almaai?

Discover more artist stories at KSA Art.